In 1850, the United States was on the edge. The North and South disagreed on slavery, money, and power. The Compromise of 1850 was a last-ditch effort to keep the country together. This blog explores the Compromise of 1850, its background, parts, effects, and why it failed to unite the North and South.

The Historical Context of the Compromise

The Missouri Compromise and Rising Tensions

Long before 1850, the North and South were divided. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 tried to balance free and slave states. It made Missouri a slave state and Maine a free state and set a line where slavery was banned (except in Missouri).

Even though the Missouri Compromise eased tensions, it didn’t solve the slavery issue in new territories. The U.S.’s westward growth and “Manifest Destiny” made this problem worse.

The Mexican-American War and New Territories

The Mexican-American War (1846–1848) changed the U.S. map. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gave the U.S. land, including California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Nevada. This sparked debates on whether these areas would allow slavery.

The Wilmot Proviso

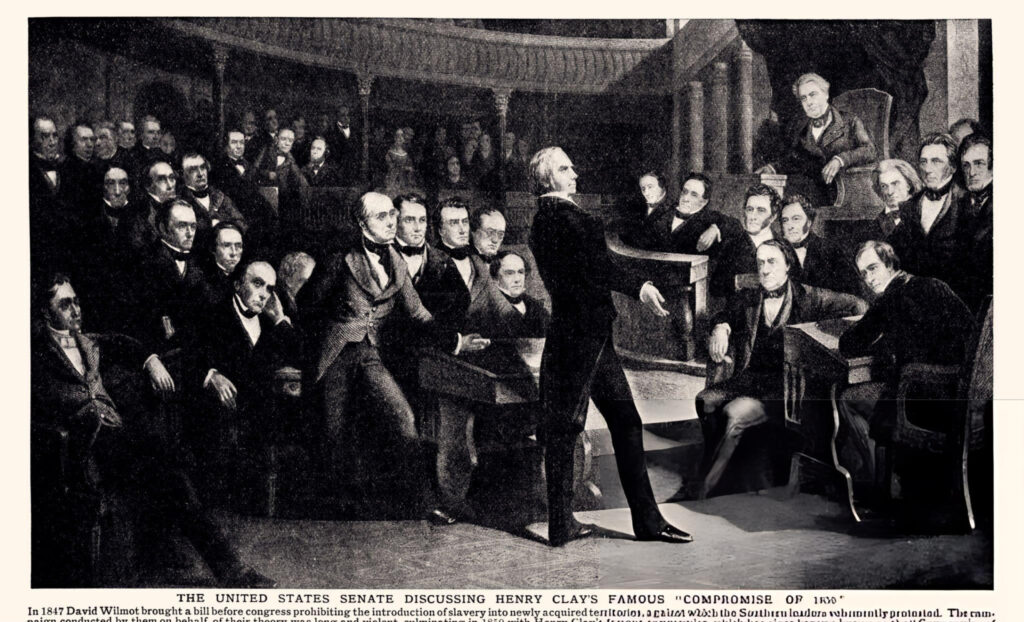

In 1846, Congressman David Wilmot proposed the Wilmot Proviso to ban slavery in Mexican territories. Though it failed, it made the North-South divide even deeper. Southerners saw it as a threat to their way of life.

The Components of the Compromise of 1850

Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky and Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois worked on the Compromise of 1850. It had five key parts:

- California Admitted as a Free State California wanted to join the Union in 1849, causing a big debate. The Compromise made California a free state, giving the North more power.

- Territorial Status and Popular Sovereignty New Mexico and Utah were organized without deciding on slavery right away. The decision would be up to the settlers, pleasing both the North and South.

- The Fugitive Slave Act The Compromise made the Fugitive Slave Act stronger. It required help in catching runaway slaves and denied them a jury trial. This upset Northern abolitionists.

- Abolition of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C. The Compromise ended the slave trade in Washington, D.C. This pleased Northerners who saw the slave markets as shameful.

- Settlement of the Texas-New Mexico Border Dispute Texas claimed land in New Mexico. The Compromise fixed the border and paid Texas $10 million to give up its claims.

Key Figures in the Compromise

The Compromise of 1850 was shaped by several key figures:

- Henry Clay: Known for his role in previous compromises, Clay introduced the initial proposals and worked tirelessly to broker a deal between the North and South.

- Stephen A. Douglas: Douglas played a critical role in passing the Compromise by breaking it into separate bills, allowing different coalitions to support individual measures.

- John C. Calhoun: A staunch defender of slavery, Calhoun opposed the Compromise, arguing that it failed to protect Southern interests adequately.

- Daniel Webster: A leading voice for the Union, Webster supported the Compromise in his famous “Seventh of March” speech, urging Northern moderates to accept concessions for the sake of national unity.

The Immediate Impact of the Compromise

The Compromise of 1850 temporarily eased tensions. It delayed the Civil War by a decade, allowing the North to industrialize further and strengthen its infrastructure, which would prove decisive in the coming conflict.

However, the Compromise also had significant drawbacks:

Strengthened Fugitive Slave Act

The Fugitive Slave Act was particularly contentious. It brought the realities of slavery into the North, where many citizens were forced to confront the moral and legal implications of the law. Northern resistance led to the growth of the abolitionist movement and the establishment of the Underground Railroad.

Popular Sovereignty and Future Conflicts

The principle of popular sovereignty, while seemingly democratic, led to violence and chaos in territories like Kansas. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and allowed for popular sovereignty in Kansas and Nebraska, resulted in “Bleeding Kansas,” a series of violent confrontations between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers.

The Legacy of the Compromise

The Compromise of 1850 is often viewed as a temporary patch rather than a lasting solution. While it delayed the Civil War, it failed to address the underlying causes of sectionalism:

Economic Differences

The North and South had fundamentally different economies. The industrial North favored tariffs and infrastructure projects, while the agrarian South relied on slavery and opposed federal interference.

Moral Divide Over Slavery

The Compromise exposed the deep moral divide over slavery. For many Northerners, the Fugitive Slave Act was intolerable, while Southerners saw the abolitionist movement as a direct threat to their way of life.

Political Fragmentation

The debates over the Compromise fractured existing political parties. The Whig Party, divided over slavery, collapsed in the 1850s, giving rise to the Republican Party, which opposed the expansion of slavery.

Lessons from the Compromise

The Compromise of 1850 highlights the challenges of addressing deeply entrenched divisions in a diverse and rapidly changing nation. It underscores the importance of confronting moral and political issues head-on rather than deferring or compromising on principles.

In retrospect, the Compromise delayed but did not prevent the Civil War. The decade that followed was marked by increasing polarization, culminating in the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and the secession of Southern states.

Conclusion

The Compromise of 1850 was a pivotal moment in American history, reflecting both the ingenuity and the limitations of political compromise. It showcased the ability of leaders like Henry Clay and Stephen A. Douglas to broker temporary peace but also exposed the deep and irreconcilable differences between the North and South.

While it succeeded in delaying the Civil War, the Compromise ultimately failed to resolve the central issue of slavery, leaving a legacy of conflict and division. Its lessons remain relevant today, reminding us of the importance of addressing systemic issues with courage, vision, and a commitment to justice.